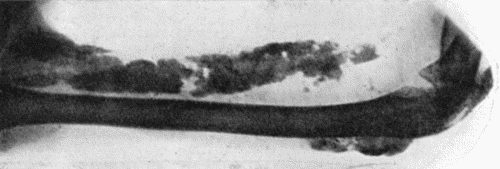

Fig. 109.—Volkmann's Ischæmic Contracture. When the wrist is flexed to a right angle it is possible to extend the fingers.

(Photographs lent by Mr. Lawford Knaggs)

Congenital absence of muscles is sometimes met with, usually in association with other deformities. The pectoralis major, for example, may be absent on one or on both sides, without, however, causing any disability, as other muscles enlarge and take on its functions.

Atrophy of Muscle.—Simple atrophy, in which the muscle elements are merely diminished in size without undergoing any structural alteration, is commonly met with as a result of disuse, as when a patient is confined to bed for a long period.

In cases of joint disease, the muscles acting on the joint become atrophied more rapidly than is accounted for by disuse alone, and this is attributed to an interference with the trophic innervation of the muscles reflected from centres in the spinal medulla. It is more marked in the extensor than in the flexor groups of muscles. Those affected become soft and flaccid, exhibit tremors on attempted movement, and their excitability to the faradic current is diminished.

Neuropathic atrophy is associated with lesions of the nervous system. It is most pronounced in lesions of the motor nerve-trunks, probably because vaso-motor and trophic fibres are involved as well as those that are purely motor in function. It is attended with definite structural alterations, the muscle elements first undergoing fatty degeneration, and then being absorbed, and replaced to a large extent by ordinary connective tissue and fat. At a certain stage the muscles exhibit the reaction of degeneration. In the common form of paralysis resulting from poliomyelitis, many fibres undergo fatty degeneration and are replaced by fat, while at the same time there is a regeneration of muscle fibres.

Fibrositis or “Muscular Rheumatism.”—This clinical term is applied to a group of affections of which lumbago is the best-known example. The group includes lumbago, stiff-neck, and pleurodynia—conditions which have this in common, that sudden and severe pain is excited by movement of the affected part. The lesion consists in inflammatory hyperplasia of the connective tissue; the new tissue differs from normal fibrous tissue in its tendency to contract, in being swollen, painful and tender on pressure, and in the fact that it can be massaged away (Stockman). It would appear to involve mainly the fibrous tissue of muscles, although it may extend from this to aponeuroses, ligaments, periosteum, and the sheaths of nerves. The term fibrositis was applied to it by Gowers in 1904.

In lumbago—lumbo-sacral fibrositis—the pain is usually located over the sacrum, the sacro-iliac joint, or the aponeurosis of the lumbar muscles on one or both sides. The amount of tenderness varies, and so long as the patient is still he is free from pain. The slightest attempt to alter his position, however, is attended by pain, which may be so severe as to render him helpless for the moment. The pain is most marked on rising from the stooping or sitting posture, and may extend down the back of the hip, especially if, as is commonly the case, lumbago and gluteal fibrosis coexist. Once a patient has suffered from lumbago, it is liable to recur, and an attack may be determined by errors of diet, changes of weather, exposure to cold or unwonted exertion. It is met with chiefly in male adults, and is most apt to occur in those who are gouty or are the subjects of oxaluric dyspepsia.

Gluteal fibrositis usually follows exposure to wet, and affects the gluteal muscles, particularly the medius, and their aponeurotic coverings. When the condition has lasted for some time, indurated strands or nodules can be detected on palpating the relaxed muscles. The patient complains of persistent aching and stiffness over the buttock, and sometimes extending down the lateral aspect of the thigh. The pain is aggravated by such movements as bring the affected muscles into action. It is not referred to the line of the sciatic nerve, nor is there tenderness on pressing over the nerve, or sensations of tingling or numbness in the leg or foot.

If untreated, the morbid process may implicate the sheath of the sciatic nerve and cause genuine sciatic neuralgia (Llewellyn and Jones). A similar condition may implicate the fascia lata of the thigh, or the calf muscles and their aponeuroses—crural fibrositis.

In painful stiff-neck, or “rheumatic torticollis,” the pain is located in one side of the neck, and is excited by some inadvertent movement. The head is held stiffly on one side as in wry-neck, the patient contracting the sterno-mastoid. There may be tenderness over the vertebral spines or in the lines of the cervical nerves, and the sterno-mastoid may undergo atrophy. This affection is more often met with in children.

In pleurodynia—intercostal fibrositis—the pain is in the line of the intercostal nerves, and is excited by movement of the chest, as in coughing, or by any bodily exertion. There is often marked tenderness.

A similar affection is met with in the shoulder and arm—brachial fibrositis—especially on waking from sleep. There is acute pain on attempting to abduct the arm, and there may be localised tenderness in the region of the axillary nerve.

Treatment.—The general treatment is concerned with the diet, attention to the stomach, bowels, and kidneys and with the correction of any gouty tendencies that may be present. Remedies such as salicylates are given for the relief of pain, and for this purpose drugs of the aspirin type are to be preferred, and these may be followed by large doses of iodide of potassium. Great benefit is derived from massage, and from the induction of hyperæmia by means of heat. Cupping or needling, or, in exceptional cases, hypodermic injections of antipyrin or morphin, may be called for. To prevent relapses of lumbago, the patient must take systematic exercises of all kinds, especially such as bring out the movements of the vertebral column and hip-joints.

Fig. 109.—Volkmann's Ischæmic Contracture. When the wrist is flexed to a right angle it is possible to extend the fingers.

(Photographs lent by Mr. Lawford Knaggs)

Contracture of Muscles.—Permanent shortening of muscles results from the prolonged approximation of their points of attachment, or from structural changes in their substance produced by injury or by disease. It is a frequent accompaniment and sometimes a cause of deformities, in the treatment of which lengthening of the shortened muscles or their tendons may be an essential step.

Myositis.—Ischæmic Myositis.—Volkmann was the first to describe a form of myositis followed by contracture, resulting from interference with the arterial blood supply. It is most frequently observed in the flexor muscles of the forearm in children and young persons under treatment for fractures in the region of the elbow, the splints and bandages causing compression of the blood vessels. There is considerable effusion of blood, the skin is tense, and the muscles, vessels, and nerves are compressed; this is further increased if the elbow is flexed and splints and tight bandages are applied. The muscles acquire a board-like hardness and no longer contract under the will, and passive motion is painful and restricted. Slight contracture of the fingers is usually the first sign of the malady; in time the muscles undergo further contraction, and this brings about a claw-like deformity of the hand. The affected muscles usually show the reaction of degeneration. In severe cases the median and ulnar nerves are also the seat of cicatricial changes (ischæmic neuritis).

By means of splints, the interphalangeal, metacarpo-phalangeal, and wrist joints should be gradually extended until the deformity is over-corrected (R. Jones). Murphy advises resection of the radius and ulna sufficient to admit of dorsiflexion of the joints and lengthening of the flexor tendons.

Various forms of pyogenic infection are met with in muscle, most frequently in relation to pyæmia and to typhoid fever. These may result in overgrowth of the connective-tissue framework of the muscle and degeneration of its fibres, or in suppuration and the formation of one or more abscesses in the muscle substance. Repair may be associated with contracture.

A gonorrhœal form of myositis is sometimes met with; it is painful, but rarely goes on to suppuration.

In the early secondary period of syphilis, the muscles may be the seat of dull, aching, nocturnal pains, especially in the neck and back. Syphilitic contracture is a condition which has been observed chiefly in the later secondary period; the biceps of the arm and the hamstrings in the thigh are the muscles more commonly affected. The striking feature is a gradually increasing difficulty of extending the limb at the elbow or knee, and progressive flexion of the joint. The affected muscle is larger and firmer than normal, and its electric excitability is diminished. In tertiary syphilis, individual muscles may become the seat of interstitial myositis or of gummata, and these affections readily yield to anti-syphilitic remedies.

Tuberculous disease in muscle, while usually due to extension from adjacent tissues, is sometimes the result of a primary infection through the blood-stream. Tuberculous nodules are found disseminated throughout the muscle; the surrounding tissues are indurated, and central caseation may take place and lead to abscess formation and sinuses. We have observed this form of tuberculous disease in the gastrocnemius and in the psoas—in the latter muscle apart from tuberculous disease in the vertebræ.

Tendinitis.—German authors describe an inflammation of tendon as distinguished from inflammation of its sheath, and give it the name tendinitis. It is met with most frequently in the tendo-calcaneus in gouty and rheumatic subjects who have overstrained the tendon, especially during cold and damp weather. There is localised pain which is aggravated by walking, and the tendon is sensitive and swollen from a little above its insertion to its junction with the muscle. Gouty nodules may form in its substance. Constitutional measures, massage, and douching should be employed, and the tendon should be protected from strain.

Calcification and Ossification in Muscles, Tendons, and Fasciæ.—Myositis ossificans.—Ossifications in muscles, tendons, fasciæ, and ligaments, in those who are the subjects of arthritis deformans, are seldom recognised clinically, but are frequently met with in dissecting-rooms and museums. Similar localised ossifications are met with in Charcot's disease of joints, and in fractures which have repaired with exuberant callus. The new bone may be in the form of spicules, plates, or irregular masses, which, when connected with a bone, are called false exostoses (Fig. 110).

Traumatic Ossification in Relation to Muscle.—Various forms of ossification are met with in muscle as the result of a single or of repeated injury. Ossification in the crureus or vastus lateralis muscle has been frequently observed as a result of a kick from a horse. Within a week or two a swelling appears at the site of injury, and becomes progressively harder until its consistence is that of bone. If the mass of new bone moves with the affected muscle, it causes little inconvenience. If, as is commonly the case, it is fixed to the femur, the action of the muscle is impaired, and the patient complains of pain and difficulty in flexing the knee. A skiagram shows the extent of the mass and its relationship to the femur. The treatment consists in excising the bony mass.

Difficulty may arise in differentiating such a mass of bone from sarcoma; the ossification in muscle is uniformly hard, while the sarcoma varies in consistence at different parts, and the X-ray picture shows a clear outline of the bone in the vicinity of the ossification in muscle, whereas in sarcoma the involvement of the bone is shown by indentations and irregularity in its contour.

A similar ossification has been observed in relation to the insertion of the brachialis muscle as a sequel of dislocation of the elbow. After reduction of the dislocation, the range of movement gradually diminishes and a hard swelling appears in front of the lower end of the humerus. The lump continues to increase in size and in three to four weeks the disability becomes complete. A radiogram shows a shadow in the muscle, attached at one part as a rule to the coronoid process. During the next three or four months, the lump in front of the elbow remains stationary in size; a gradual decrease then ensues, but the swelling persists, as a rule, for several years.

Fig. 111.—Calcification and Ossification in Biceps and Triceps.

(From a radiogram lent by Dr. C. A. Adair Dighton.)

Ossification in the adductor longus was first described by Billroth under the name of “rider's bone.” It follows bruising and partial rupture of the muscle, and has been observed chiefly in cavalry soldiers. If it causes inconvenience the bone may be removed by operation.

Ossification in the deltoid and pectoral muscles has been observed in foot-soldiers in the German army, and has received the name of “drill-bone”; it is due to bruising of the muscle by the recoil of the rifle.

Progressive Ossifying Myositis.—This is a rare and interesting disease, in which the muscles, tendons, and fasciæ throughout the body become the seat of ossification. It affects almost exclusively the male sex, and usually begins in childhood or youth, sometimes after an injury, sometimes without apparent cause. The muscles of the back, especially the trapezius and latissimus, are the first to be affected, and the initial complaint is limitation of movement.

Fig. 112.—Ossification in Muscles of Trunk in a case of generalised Ossifying Myositis.

(Photograph lent by Dr. Rustomjee.)

The affected muscles show swellings which are rounded or oval, firm and elastic, sharply defined, without tenderness and without discoloration of the overlying skin. Skiagrams show that a considerable deposit of lime salts may precede the formation of bone, as is seen in Fig. 111. In course of time the vertebral column becomes rigid, the head is bent forward, the hips are flexed, and abduction and other movements of the arms are limited. The disease progresses by fits and starts, until all the striped muscles of the body are replaced by bone, and all movements, even those of the jaws, are abolished. The subjects of this disease usually succumb to pulmonary tuberculosis.

There is no means of arresting the disease, and surgical treatment is restricted to the removal or division of any mass of bone that interferes with an important movement.

A remarkable feature of this disease is the frequent presence of a deformity of the great toe, which usually takes the form of hallux valgus, the great toe coming to lie beneath the second one; the shortening is usually ascribed to absence of the first phalanx, but it has been shown to depend also on a synostosis and imperfect development of the phalanges. A similar deformity of the thumb is sometimes met with.

Microscopical examination of the muscles shows that, prior to the deposition of lime salts and the formation of bone, there occurs a proliferation of the intra-muscular connective tissue and a gradual replacement and absorption of the muscle fibres. The bone is spongy in character, and its development takes place along similar lines to those observed in ossification from the periosteum.

Tumours of Muscle.—With the exception of congenital varieties, such as the rhabdomyoma, tumours of muscle grow from the connective-tissue framework and not from the muscle fibres. Innocent tumours, such as the fibroma, lipoma, angioma, and neuro-fibroma, are rare. Malignant tumours may be primary in the muscle, or may result from extension from adjacent growths—for example, implication of the pectoral muscle in cancer of the breast—or they may be derived from tumours situated elsewhere. The diagnosis of an intra-muscular tumour is made by observing that the swelling is situated beneath the deep fascia, that it becomes firm and fixed when the muscle contracts, and that, when the muscle is relaxed, it becomes softer, and can be moved in the transverse axis of the muscle, but not in its long axis.

Clinical interest attaches to that form of slowly growing fibro-sarcoma—the recurrent fibroid of Paget—which is most frequently met with in the muscles of the abdominal wall. A rarer variety is the ossifying chondro-sarcoma, which undergoes ossification to such an extent as to be visible in skiagrams.

In primary sarcoma the treatment consists in removing the muscle. In the limbs, the function of the muscle that is removed may be retained by transplanting an adjacent muscle in its place.

Hydatid cysts of muscle resemble those developing in other tissues.